The AI Onion: A Layered Approach to AI Integration

An Inspiration

My mom came from a family of sharecroppers in Southern Maryland. She grew up in a tiny house with seven siblings who all spent long, hot summers working in tobacco fields. Harvesting tobacco is backbreaking labor: you bend all the way to the ground, grab the tobacco by the stalk, and slice it off with a sharp little ax. She loved her family, but was determined to get out of there and find a better life for herself.

She was the first of her family to go to college - the first in 300 years of tobacco farming in America. She wanted to major in math, and she recounted often her high school math teacher who told her “girls can’t do math.” Well, that motivated her all the more. She graduated college in three years and went on to complete a Masters in biostatistics at Johns Hopkins.

I will take any opportunity to brag about my mom, and I promise this connects to AI, so bear with me!

A biostatistician is essentially a data scientist for medicine. At work in a research hospital, my mom designed clinical trials and analyzed the data. The mission was to determine whether treatments under trial actually worked to improve patient outcomes. Her job was epistemological: how do we know a treatment is working? How do we know what we know?

Growing up, I absorbed this way of thinking. My mom would point to a chart in USA Today and explain why it was misleading. “This sample size is too small to tell you anything significant!” I came to believe there’s a big divide between people who think statistically and those who don’t. Statistical thinking is about being rigorous with evidence, understanding confidence intervals, knowing when you can trust a claim and when you can’t.

My mom passed away two years ago from triple negative breast cancer. She fought for three and a half years. And in the end she “lost” that fight. But I prefer to look at it like the late, great comedian Norm Macdonald: you can’t really lose to cancer: when you die, the cancer dies too. That’s a draw.

So, no, she never truly lost. She fought until the end by doing her own research. Every day she was busy looking into clinical trials and experimental therapies. Her background in biostatistics informed and emboldened her. She knew how to read the literature, how to assess whether a study was well-designed, how to weigh the evidence.

She declined and died just as ChatGPT was gaining traction.

She would have been fascinated by what generative AI can do and its statistical underpinnings. She would have used these tools to dig deeper into the research. And who knows, maybe there actually was a treatment path for her that AI could have helped her discover, had it been available then as it is now.

That question is what drew me to partner with a world-class oncologist on an AI cancer research assistant we are developing together. Both biostatistics and modern AI are tools for expanding what we can know from large amounts of data. They share the same mission my mom dedicated her life to: how do we know this treatment works for this patient?

Often I think: Could AI actually cure cancer? What a huge question. I don’t know. Maybe not today, maybe not in five years. But based on what I’m seeing, I’m beginning to think it could. Even if that’s too ambitious, what AI can do right now is help an oncologist cure cancer for an individual patient - for someone with an amazing story like my mom, who deserves a little more time.

For this reason, I want to help others understand the potential of AI. To that end, I’ve developed a framework I want to share with you: the AI Onion.

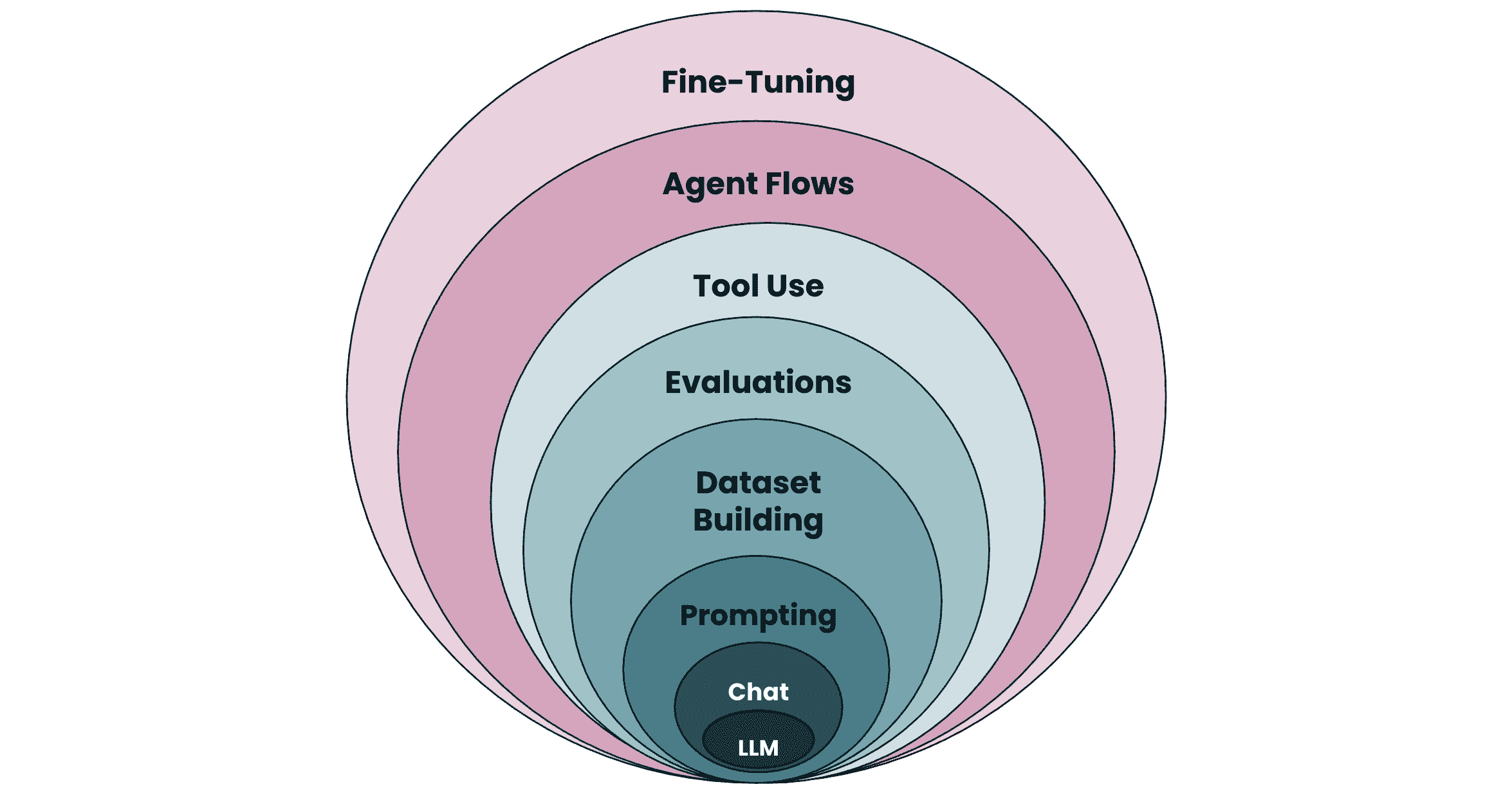

The AI Onion

Founders often come to me saying “I want to build an AI agent” or “I need to fine-tune a model so I have solid IP to show investors.” They are starting from the outside of the problem, the most complex and most expensive layers, without having thought through the fundamentals.

This is backwards. Here’s the thing: technology is not your business. It’s your organization, your relationship with the people you serve, your ability to create real-world outcomes like saving patients’ lives. That’s where the value is. Technology just speeds things up and amplifies what’s already there.

So when a founder comes to me wanting to build an AI agent, I want to know: what outcome are you trying to drive? What problem are you solving for real people? For instance, founders don’t usually know to ask for evals (which we’ll talk about in a moment). And, sure, we could fine-tune a model on a dataset that’s too small or nonsensical, but we have too much integrity to just do what we’re asked without questioning whether it makes sense.

For the cancer research assistant, it’s all about improving patient outcomes. Over the long run, we’ll measure that. In the near term, we use experts to verify that the outputs are reasonable, correct, and providing value by performing time-consuming research that reliably unveils hidden gems of insight.

Any complex system that works is built up from simpler systems that work. You have to start from the core and work outward, adding complexity only when you’ve hit the limits of the current layer.

I think of it like a chef planning the courses of a meal: what should come out when, how should the flavors be composed and timed to maximize impact. Hence the AI Onion.

The AI Onion is the framework I developed to sequence these conversations. It’s a mental checklist I use when working through a new founder’s problem, starting from the inside out. Some founders are savvy and have already resolved the inner layers. Others need more hand-holding. But everyone benefits from making sure the foundations are solid before building upward.

The goal is minimum investment for maximum impact. Start at the core, verify it works, and only add outer layers as needed.

Layers 1-2: Foundation Model and Chat Interface

At the heart of the onion is the large language model, a machine learning model trained on what people like to say is “all the text on the internet.” You won’t build your own; this costs millions of dollars. You buy it off the shelf from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, or Meta. That’s why we call these foundation models.

The next layer is the chat interface, the back-and-forth interaction pattern that made ChatGPT explode into mainstream consciousness. You won’t build this from scratch either.

But these layers still matter for decision-making. Different foundation models have different personalities, capabilities, and cost structures. ChatGPT is often the default, but some projects have requirements that suggest an open-source model or a secure environment like AWS Bedrock. There is a lot to talk about here, and we have various frameworks to support the decision process.

As for chat, while most AI applications look like “chatbots” to end users, many wrap the LLM in a service that takes advantage of chat functionality “behind the scenes.” They take advantage of system prompts and user/agent exchanges without exposing a chat interface at all. It’s not a chatbot, but it’s still an “AI tool.”

For the cancer research assistant, we started with ChatGPT as our foundation model and have since added Gemini for large context analysis. We are trying to build such that we are not locked into the same LLM over the long run. We have a hybrid conversational interface for exploratory research and a behind-the-scenes engine that does constant background research and generates structured patient reports. Clinicians receive real-time updates and insights about the latest research relevant to their patients. They don’t have to actively seek it out.

These are the first questions to resolve: Which model? What interaction pattern? Get these right before moving outward.

Layer 3: Prompting

This is where the real work begins.

LLMs know everything about everything. They’ve seen the whole internet. They can talk like Neil deGrasse Tyson about space, like Shakespeare, or like a pirate. What you need to do is focus them on what you care about.

The way this works is you provide the LLM with a system prompt. For the cancer research assistant, our system prompt starts: “You are a cancer research assistant.” That sentence alone focuses the LLM’s vast knowledge on cancer and establishes its role. The LLM is very good at stepping into a role like this. Then we define its goal: “You’re going to assess and score research articles based on their potential clinical relevance.” We specify the dimensions we care about: diagnostic, therapeutic, prognostic, mechanistic.

Some founders come to the table with prompts already prepared. Others need to understand how to write a good prompt and the implications of the LLM’s probabilistic nature: it might go in different directions each time, it might occasionally make things up.

Prompting may be all you need. Depending on your use case, a well-crafted prompt against an off-the-shelf LLM might get you 80% of the way there. LLMs are remarkably capable and knowledgeable. Before adding complexity, verify that prompting alone isn’t sufficient.

Layer 4: Dataset Integration

Sometimes prompting isn’t enough, and you need to bring proprietary data (or a specialized approach to public data) into the conversation.

This is where things heat up. Prompts add value, but specialized data is where you start building something that’s your own, something nobody else can exactly replicate.

At this layer, we fetch the data and hand it to the LLM. This is traditional software and data pipelines doing the work: a SQL query that grabs a patient record, an API call that retrieves relevant documents, a vector search that pulls context from unstructured assets in your knowledge base. We can inject that context into the prompt before the LLM ever sees it. The LLM doesn’t know where the information came from; it just sees enriched context.

For the cancer research assistant, this means patient context: their genetic profile, their diagnosis, their treatment history, combined with public literature via our proprietary prompting approach. The oncologist I’m working with on this project helps write some of the national standards for cancer treatment. He says this is necessary because clinicians were trained 10, 15, 20 years ago and they’re treating patients today. The research has changed dramatically, and they’re not up to date on the latest literature.

He likes to say that “cancer is not one disease, it’s a million diseases.” Every patient’s case is different. The knowledge to help them often exists somewhere in the research literature. The hard part is sifting through it all to find what’s relevant to this patient. That’s what AI is good for: crunching through vast amounts of data to map a particular case to the wealth of research that’s out there.

If they had a tool that could correlate a patient’s specific case with current research, they could very likely identify treatment paths today that they couldn’t have just a few years ago.

The key distinction: at Layer 4, we’re still in control of what data gets fetched and when. The LLM receives context; it doesn’t go looking for it.

Layer 5: Evaluations

At this point you have a foundation model, an interaction pattern, a prompting strategy, and integrated data. Only now can you have a productive conversation about evaluations.

Evals are a cross-cutting concern; in theory, you should be evaluating at every layer. But in practice, if a team hasn’t resolved the layers below, it’s not possible to build formal evaluations. You can’t define what “correct” looks like until you know what you’re building and why it’s valuable.

LLMs are probabilistic. Sometimes they give you the perfect answer. Sometimes they make things up. At the lower layers, you can get by on vibes: “This feels right. I’ve talked to it a lot and it seems 80% there.” In the early stages of our cancer research app, we asked a trained oncologist to check the vibe of our assistant. Even if it was not 100% correct, is it significantly better than random chance and heading in the right direction?

Evaluations are how you get from 80% to 95% to close to 100%. In mission-critical situations like cancer research, you want structured tests you can run automatically, with clear pass/fail criteria based on whether the output matches what it should be.

Evaluations are tests of whether the system’s behavior aligns with what you hoped it would do.

For the cancer research assistant, this means: Does it surface the most relevant articles? Does it extract and accurately interpret information from our database? Does it score research appropriately on the four dimensions that matter to us? Does it avoid hallucinating citations? We build test cases with known-good answers and run them against the system continuously as we add capabilities.

This is where rigor enters the picture. If you skipped here from Layer 1, you’d have nothing concrete to evaluate. And from here on out, maintaining and growing your set of evaluations is critical to ensuring that your AI solution works as intended.

Layer 6: Tool Use

At Layer 6, we begin to give the LLM tools so it can decide what to fetch for the user.

This is your first taste of agentic capabilities. You give the LLM access to functions it can call: search a database, hit an API, create a new patient record, retrieve a document. The LLM decides when to use these tools based on the conversation.

For the cancer research assistant, we gave it tools to search PubMed and a variety of other research datasets. For example, when a user asks “Please research the role of PTEN in triple negative breast cancer,” the LLM formulates its own search query, calls the PubMed tool, gets back hundreds of articles, reads through them, ranks and scores them, and presents the most relevant results. All this happens in about 15 seconds. And it’s incredible the kinds of connections the AI can make across a wide array of literature, almost instantly.

The oncologist I’m working with told me: “To do this three years ago, I had to open hundreds of browser tabs. I had to brute force the whole thing, spend hours pouring through literature.” Now it’s at his fingertips.

Tool use opens up significant capability, but it also introduces even more unpredictability. The LLM might call tools in unexpected ways or sequences. This is why Layer 5 (Evaluations) must be considered first. You need the infrastructure to test whether tool use is behaving correctly before you ship it.

Layer 7: Agent Flows

Layer 6 gave the LLM tools. Layer 7 chains those tools together into complex workflows, with the LLM reasoning through multi-step processes, and even coordinating with other agents.

This is where a single user input might set off a cascade: multiple prompts, many tool calls to different services, intermediate reasoning steps, even separate agents collaborating. At this layer, the system becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

The patient report feature is a good example. When I click “generate new report,” I don’t type anything into a chatbot. The system takes the patient’s genetic profile, sends it to the LLM, which then autonomously searches PubMed for each relevant genetic mutation. It reads and scores the articles, cross-references with active clinical trials, and assembles a structured report with citations. It just thinks independently, guided by prompts and workflows that mimic how a real oncologist would do their research. When it’s done, it comes back with a complete report.

The busy oncologist walking down the hallway to an appointment can consult this report and step into that meeting with a more informed recommendation than would have been possible before.

This is the current frontier of AI: delegating entire tasks and waiting for results. It’s powerful, but it’s also the most difficult to test and the most prone to unexpected behavior. Going back to the principle of building complex systems from simple systems, you can see why this must be an outer layer. The lower layers are the simpler components that have to be solid first: foundation model, prompts, data integration, evaluations, tool use. These are what the agent flow is composed of.

If a founder wants to jump straight to “I want an agent,” this is where I slow them down. Have we resolved the inner layers that will comprise it? Do we have evaluations in place? Agents are not magic. They’re orchestrations of simpler pieces.

A meta point here: when I first developed this framework in early 2025, agents were not as mature as they are now. Today, every off-the-shelf LLM has agentic capabilities built in: they can search the web, complete multiple reasoning steps, use tools. But if you’re building your own AI application, you need to understand the difference between the core LLM and the agentic capabilities layered on top. The onion helps you see those layers distinctly and think about how you can customize an agent for your own purposes by defining its tools, prompts, and workflows, rather than relying on the “one size fits all” solutions in the market.

Layer 8: Fine-Tuning

Finally, fine-tuning means training your own version of a foundation model. Not from scratch, but adapting an existing model with your own data to reshape its behavior for your specific use case.

I’ve had founders come to me wanting to fine-tune right away. “We need our own model for IP reasons.” I get it, and it’s a smart end goal, but nine times out of ten, they haven’t even thought through Layers 1-5. What foundation model will you fine-tune and why? Will you fine-tune for chat or something else? Fine-tuning requires a robust dataset of examples. Where does that dataset come from? How will you evaluate that your fine-tune was successful? From running the system, collecting outputs, evaluating them, refining them. You need most of the lower layers in place before you have the data and evaluation clarity to fine-tune meaningfully.

And to be honest, very few teams actually need this layer. Most get what they need from prompting through tool use. Fine-tuning is a tool in your toolbox, but it’s rarely the right first move.

The Point

The AI Onion exists because founders kept trying to peel the problem from the outside in. They jump to agents, fine-tuning, complex architectures before appreciating the components from the bottom up.

The framework is a sequence for working through the problem correctly. Which foundation model? What interaction pattern? Can prompting alone get us there? What data do we need to integrate? How will we evaluate success? Only then can we approach the thornier issues: should the LLM have tools? Should we build agent flows? Do we actually need to fine-tune?

For the cancer research assistant, we worked through each layer in order and we now have a very robust multi-agent architecture that we can rigorously evaluate. Foundation model and interface. Prompts that define the research methodology. Patient context integrated with public literature. Evaluations to verify accuracy. Tools for the LLM to search PubMed autonomously. Agent flows to generate complete patient reports without human intervention.

Each layer was added because the previous layer wasn’t sufficient, not because it seemed impressive. Because we built up this complex system from simple components, we know that it works, and we know how we know.

The doctor I’m working with is very excited about where this is going. And I think about my mom. She would have loved this tool. She would have used it to dig deeper into the research, to find angles her oncologists might have missed.

She deserved a little more time. Maybe tools like this will help give that time to someone else.